Don's Weekly Listen: Kalinnikov 1

Happy Monday! To the many who have joined The Podium community since the publication of our “Price of Equity” series, welcome!

In the third part of that series, I advocated for a perpetually open classical music canon. I argued that it is our duty both as musicians and as listeners to keep the canon fresh by continuously listening to music we don’t know. It is true, I will grant, that many pieces of unfamiliar music are unfamiliar for good reason. But there are also thousands of composers and works whose unfamiliarity to us is a simple accident of history. Making those discoveries is one of the most rewarding things about being a classical musician or listener.

In that spirit, I am launching a weekly newsletter (in addition to my monthly long-form articles) in which I will send you a recording of a piece of music that I believe deserves wider recognition, accompanied by a brief introduction. I hope that an extra bit of quality listening material will both brighten your Monday, and suggest new directions in your own listening.

First up on Don’s Weekly Listen is the First Symphony of Vasily Kalinnikov (1866-1901).

Most composers in tsarist Russia who did not come from aristocratic backgrounds were consigned to the margins of the music scene. But despite dropping out of Moscow Conservatory due to his inability to pay the tuition (Kalinnikov’s father was a policeman), the prodigious young musician persevered, earning a living as a bassoonist, violinist, timpanist, and music copyist. He eventually caught the attention of Tchaikovsky, who was harmony and theory professor at the school Kalinnikov had been unable to afford.

Seeking to advance the young composer’s career, the master recommended him at age 24 for a conducting position at the Maly Theater in Moscow, but Kalinnikov was forced to leave the job quickly due to ill health. Suffering from advancing tuberculosis, the young composer moved to Crimea for the warm climate, where he lived out the remaining ten years of his life and wrote music for publication, including two symphonies.

Kalinnikov wrote the first of these symphonies in 1894 and 1895. While still regularly performed east of the new Iron Curtain, it rarely appears on American stages nowadays. In listening to it, you’ll wonder why.

You will be struck right away both by the symphony’s warm-heartedness and its grandeur. The symphony’s musical language owes a great deal both to the irrepressible melodiousness of Tchaikovsky and the more rustic Russian stylings of Borodin and Balakirev. You will notice the frequent use of repeated small melodic cells (ostinati) to build tension, e.g., at 35:30, anticipating similar devices in Stravinsky’s revolutionary Firebird almost 20 years later.

Kalinnikov achieves in this symphony an impressive degree of large-scale unity and coherence. You will, for instance, hear the contemplative theme of the second movement recast as the redemptive climax of the finale, and the slithering chromatic passage from the main theme of the first movement transformed into the propulsive introduction to the fourth movement. The result is a Schumannesque unity of materials that multiplies the emotional impact of this work exponentially.

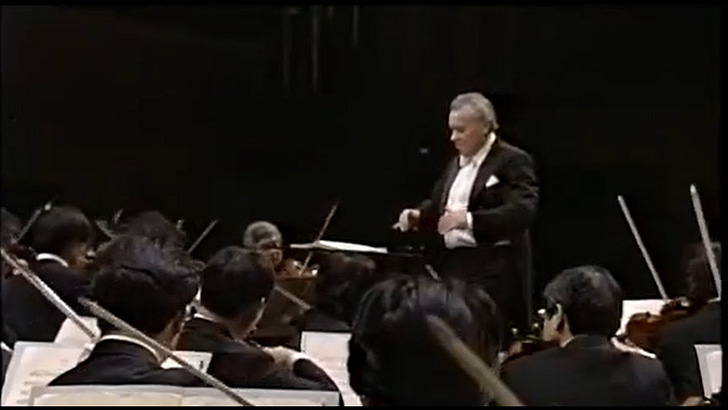

The attached recording is a classic live performance by Japan’s NHK Symphony orchestra, conducted by the great Soviet Maestro Yevgeny Svetlanov. Please enjoy, and share this newsletter with any friends and colleagues who might enjoy hearing some music and getting the inside track on the classical music industry, minus the political correctness.

Have a great week!

DB