When I (and many of you, I imagine) learned music history in school, there seemed to be a massive, unbridgeable valley between the classical and romantic periods. On one bank of this chasm were those late classicists who, with a great heave of individual will, forked off from the narrow path of classical form into the wilderness of self-expression. Here I refer to Beethoven and Schubert. On the other were the unabashed romantics—names like Schumann, Chopin, Berlioz, and Liszt. Both groups reached out over the abyss to grasp one another’s hands, but came up empty.

When I started learning the repertoire for myself, I discovered that this chasm in my knowledge was due mainly to music history’s neglect of a group of hugely consequential composers in the 1820s and 1830s. Some of these composers, like Carl Maria von Weber, are acknowledged in the history books but downplayed in their significance. Others are written out of music history almost entirely.

There is no more egregious case of the latter, in my view, than that of Johann Nepomuk Hummel. Despite being an epochal talent who played a significant role in shaping the early romantic period, Hummel barely rates a mention on the pages of music history texts read by American undergraduate and graduate music students.

It is no surprise, given that yesterday’s music students end up running today’s concert series and performance halls, that most music lovers who attend concerts in those venues don’t know much about him either. (Indeed, the only time they are liable to hear Hummel’s work in a symphonic concert nowadays is when a trumpet virtuoso comes to town and requests to play the Hummel Concerto.)

Johann Hummel was born in 1778 in Pressburg, Austria (today, the Slovak capital of Bratislava). At a tender age, Hummel showed signs of musical prodigy. At eight years old, he became a private student (and boarder) of Mozart in Vienna. As he grew up, he became known as Europe’s preeminent piano virtuoso. He forged professional relationships and personal friendships with virtually all the great musical names of his time, including Beethoven. The two had a tumultuous relationship (as Beethoven did with virtually everyone he knew), but ultimately reconciled, with Hummel serving as a pallbearer at Beethoven’s funeral.

One significant difference between Hummel and both his mentor Mozart and friend Beethoven is that he had a keen eye for business. His efforts were central in the establishment of multinational publication standards for sheet music and a single copyright protection zone throughout the German-speaking world. These developments were vital in transforming the composer’s role from indentured artisan to individual creator, and they redounded greatly to Hummel’s own financial benefit. Perhaps detrimentally to his reputation in our time, Hummel, unlike storybook heroes Mozart and Beethoven, died a wealthy man.

When he died in 1837, Hummel left behind a treasure trove of inventive music straddling the boundary between the classical and romantic eras. In order to appreciate his impact, there is no better place to start than his six piano concertos, out of which I propose two listens in particular.

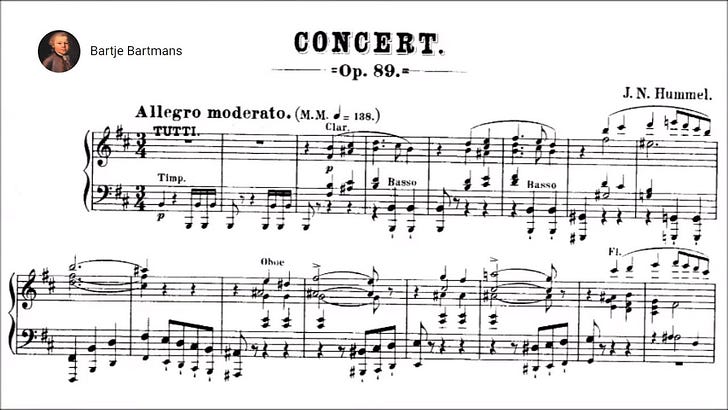

The first is his Piano Concerto No. 3 in B Minor. As the only classical period concerto I know of to start with a timpani solo, it will grab you from the first bar and hold your attention through a sophisticated 35-minute arc.

This piece, more than any other of Hummel’s, brought me to a realization about its composer’s role in music history. That is: that there are two main avenues by which classical became romantic. One line led from Beethoven’s heroic style through the operas of Weber, toward (forking off in different directions) Wagner and Brahms. The other line led from the sturm und drang expressiveness of Haydn and lesser-known classical composers like Dittersdorf and Dussek, through Hummel, toward Schumann and Chopin. In Hummel’s B Minor Concerto, you can see this process in action. If you’re looking for Chopin in embryo, cue up 21:20-23:20—the wistful climax of the slow movement’s development section—in the attached video.

The other listen I recommend is the final movement of Hummel’s posthumously published F Major Piano Concerto. The first two movements are somewhat pedestrian, but the last movement is a late classical romp nonpareil. Cue up the video to 20:15. You’ll be in for a raucous seven minutes, combining a whirling waltz with martial polonaise rhythms. This movement will also provide you with a trivia question you can pull out with your musically-minded friends: “Name a concerto that ends with a plagal (IV-I), or ‘Amen’ cadence.” This is the only one I know of.

In fact-checking this article in Oxford Music Online (which I usually do to ensure I’m not disseminating fake news), I was delighted to find that Joel Sachs and Mark Kroll, authors of Oxford’s article on Hummel, shared my opinion on his underappreciated impact. I quote them here:

It is through Hummel, not Beethoven, that may be seen the crucial transformation in which the old virtues of clarity, symmetry, elegance, restraint and ‘learnedness’ yielded to the new ‘inspiration’, emotionalism, commercialism and showmanship. As one of the last and greatest representatives of the 18th-century Viennese classical style that created him, Hummel played a vital and still largely unacknowledged role in creating the new romantic style of the 19th century.

Enjoy, and have a great week!

DB

Thank you so much for bringing Johann Nepomuk Hummel to your readers' attention!

I absolutely adore Hummel! I wish his music were performed much more often and that he were regarded much more highly by the classical music establishment / academy.

I tried to request the biography by Mark Kroll from the LINK+ interlibrary borrowing system, but evidently only one library in the entire library ecosystem in which my local libraries participate (in California) even owns the book; it's stashed away in that library's basement, (that's precisely what the internet listing says about its location), and it's unavailable to be lent out to anyone! However, I was able to request Joel Sachs's biography (Kappelmeister Hummel in England and France) and I plan to read that.

In searching for those two biographies, I learned that Hummel wrote a four volume treatise on the art of playing keyboard instruments. I'm paraphrasing C.P.E. Bach's title for his own treatise, which (translated into English) is Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments, which I read many years ago and still own to this day. I requested one volume of Hummel's treatise, too, out of curiosity about what he wrote. (The library system only allowed me to request one of the four volumes.)

I'm actually very curious to see what Hummel says in this book. I was into authentic performance practice before most of my peers, when I was a teenager, in the late 1960s and 1970s, and I retrained myself to play the piano in a stylistically more authentic manner than the way I'd been taught. I wish I'd owned a piano created in the style of the keyboard instruments that were being crafted in the early-to-mid-1800s.

This is related to something I thought of writing in the comments section following one of your recent posts, but didn't at the time. You wrote something somewhat derogatory about Schumann's ability to orchestrate effectively or imaginatively. (I'm paraphrasing; I don't recall the exact words you used.) My response was and is that if one listens to Schumann's orchestral works played on authentic instruments of his day, and conducted at appropriately lively tempi, by musicians who play in stylistically accurate ways in terms of phrasing, articulation, etc., Schumann's symphonic works are crystal clear, vibrant, indescribably intense and alive, brilliant and emotionally moving beyond belief.

I'm not so much a fanatic about playing on authentic instruments as to believe or say that musical compositions should only be played on stylistically correct instruments, but I do think that they can only be fully appreciated when played on authentic instruments, by musicians who are trained in the performance techniques of the era in which the music was composed.